Tratamiento de rescate sin demora

Las opciones de tratamiento de rescate son intervenciones que

no se han aplicado antes o en las que la vida media sugiere que

ya no son activa

s 190 .Los antagonistas de la serotonina, si no se

administraron en el quirófano, pueden ser el primer tratamiento

en la URPA ya que carecen de efecto sedante. También, aña-

diendo dexametasona al dolasetrón o al haloperidol pueden

aumentar la reducción global de riesgo de precisar tratamiento

de rescate (de nuevo, si no se ha administrado antes

) 193 .Final-

mente, la estimulación del punto P6 de acupresión puede ser una

opción válida, ya que ha demostrado ser eficaz en la prevención

de las NVPO.

Bibliografía

1. Dolin SJ, Cashman JN, Bland JM: Effectiveness of

acute postoperative pain management: I. Evidence

from published data. Br J Anaesth 89:409-423, 2002.

2. Palazzo M, Evans R: Logistic regression analysis of

fixed patient factors for postoperative sickness: A

model for risk assessment. Br J Anaesth 70:135-140,

1993.

3. CohenMM, Duncan PG, DeBoer DP,

TweedWA:Thepostoperative interview: Assessing risk factors for

nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 78:7-16, 1994.

4. Koivuranta M, Laara E, Snare L, Alahuhta S: A

survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Anaesthesia 52:443-449, 1997.

5. Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, et al: A simplified

risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and

vomiting: Conclusions from cross-validations

between two centers. Anesthesiology 91:693-700,

1999.

6. Eberhart LHJ, Hogel J, Seeling W, et al: Evaluation

of three risk scores to predict postoperative nausea

and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 44:480-488,

2000.

7. Visser K, Hassink EA, Bonsel GJ, et al: Randomized

controlled trial of total intravenous anesthesia with

propofol versus inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane-

nitrous oxide: Postoperative nausea with vomiting and

economic analysis. Anesthesiology 95:616-626, 2001.

8. Stadler M, Bardiau F, Seidel L, et al: Difference in

risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Anesthesiology 98:46-52, 2003.

9. Watcha MF, White PF: Postoperative nausea and

vomiting: Its etiology, treatment, and prevention.

Anesthesiology 77:162-184, 1992.

10. Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A: Which

clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to

avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg

89:652-658, 1999.

11. Gan T, Sloan F, Dear G, et al: Howmuch are patients

willing to pay to avoid postoperative nausea and

vomiting? Anesth Analg 92:393-400, 2001.

12. Kerger H, Turan A, Kredel M, et al: Patients’ willing-

ness to pay for anti-emetic treatment. Acta Anaes-

thesiol Scand 51:38-43, 2007.

13. Darkow T, Gora-Harper ML, Goulson DT, Record

KE: Impact of antiemetic selection on postoperative

nausea and vomiting and patient satisfaction. Phar-

macotherapy 21:540-548, 2001.

14. Bremner WG, Kumar CM: Delayed surgical emphy-

sema, pneumomediastinum and bilateral pneumo-

thoraces after postoperative vomiting. Br J Anaesth

71:296-297, 1993.

15. Schumann R, Polaner DM: Massive subcutaneous

emphysema and sudden airway compromise after

postoperative vomiting. Anesth Analg 89:796-797,

1999.

16. Gold BS, Kitz DS, Kecky JH, Neuhaus JM: Unanti-

cipated admission to the hospital following ambu-

latory surgery. JAMA 262:3008-3010, 1989.

17. Hill RP, Lubarsky DA, Phillips-Bute B, et al: Cost-

effectiveness of prophylactic antiemetic therapy

Náuseas y vómitos postoperatorios

2517

76

Sección VI

Cuidados postoperatorios

© ELSEVIER. Fotocopiar sin autorización es un delito

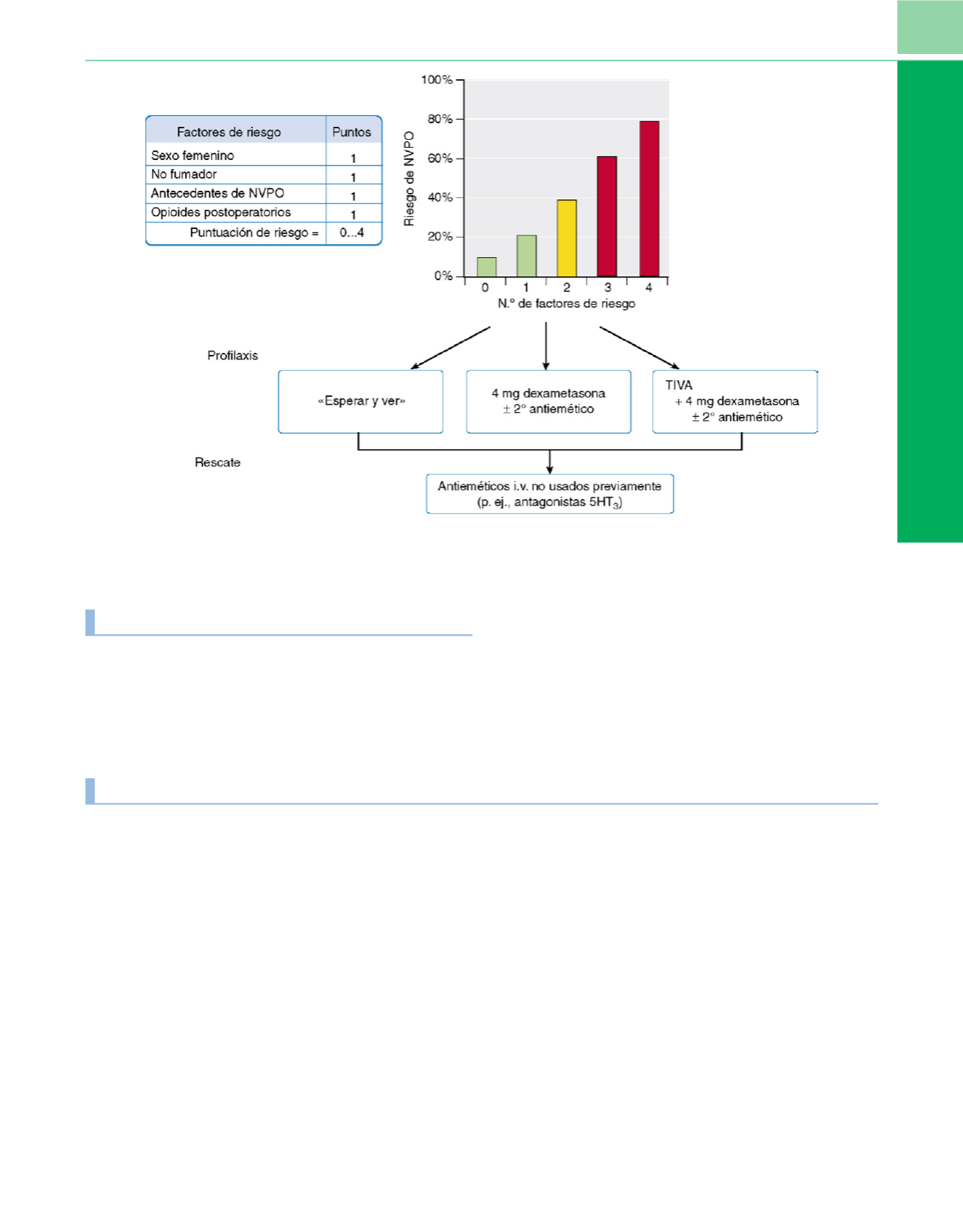

Figura 76-14

Algoritmo para el tratamiento del las NVPO.